Introduction

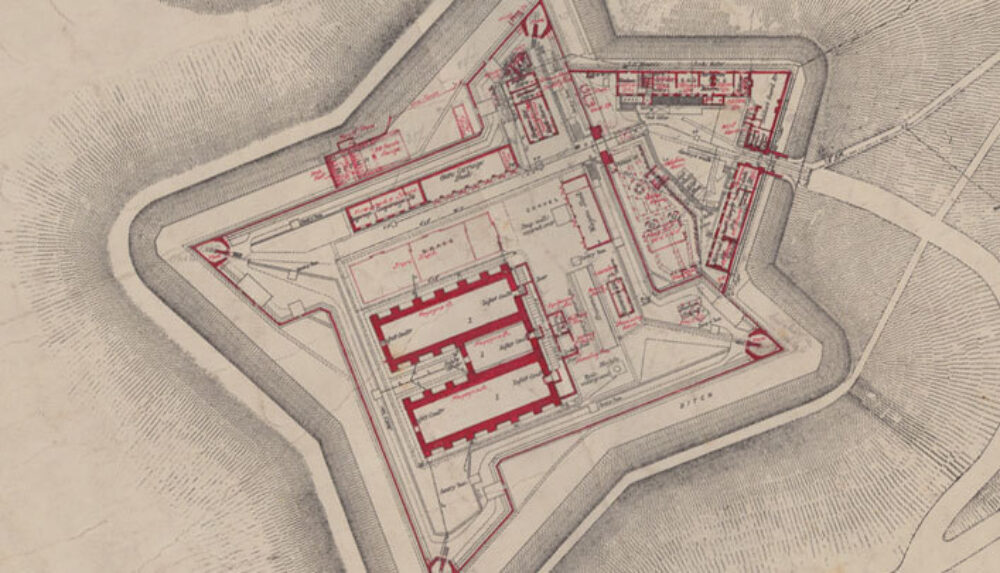

The Maps, Plans and Drawings collection of Military Barracks and Posts in Ireland (MPD Collection) is one of our newest online resources for researchers. Taken from a collection of 19th and 20th century paper architectural maps, plans and drawings of military installations throughout the island of Ireland — many of which are previously unseen - it offers a unique opportunity to explore Ireland’s military architectural heritage.

The MPD collection has come from a variety of sources, both under the British (UK) and Irish (Free State and Republic) administrations. The vast majority of Ireland’s surviving military installations (north and south of today’s border), including barracks, posts, camps, forts and castles, were constructed by the British during the 19th century. Accordingly, most of the MPD records were originally produced for the War Office (contemporary Department of Defence equivalent) by the Royal Engineer Corps of the British Army, mainly from the Southampton drawing offices, but often in conjunction with the Ordnance Survey offices at Mountjoy Barracks in the Phoenix Park Dublin, which today houses the Ordnance Survey of Ireland. These barracks were constructed under the auspices of such Crown organisations as the Board of Public Works and later the Barracks Board.

A brief history of barracks in Ireland

A number of reports into the health of soldiers and the financial expenditure on barrack buildings and repair in Ireland were drafted for the British House of Commons throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to an 1847 report, which tabulates details of 138 barracks in Ireland , thirty-five had been constructed before 1791, sixty-eight between 1791 and 1815 (the Napoleonic era) and sixteen after 1815. The geographical distribution, by province, was:

- Ulster — 28

- Leinster — 35

- Munster — 54

- Connaught — 23

The oldest barracks mentioned in the report, Elizabeth Fort in the Cork District, is described as having been erected “in the 16th century”, had sleeping accommodation for thirty-three non-commissioned officers and privates, had no washing facilities for men and was, in 1847, “occupied by police”. Perhaps the most famous Irish barracks, certainly the most famous in Dublin, was the Royal (and from 1922 Collins) barracks, which is now a site for the National Museum of Ireland, housing the Soldiers and Chiefs exhibition. Construction of the Royal Square, part of the Royal Barracks, Dublin, commenced in 1701 and by Act of Parliament of 1707 “...all officers, soldiers, troops and companies in her Majesty’s Army … shall be lodged in the barracks … instead of being accommodated in the public taverns and alehouses within the city” . The Palatine Square was added in 1767, the hospital in 1790 and the remaining buildings in 1825. By 2001, when the 5th Infantry Battalion and 2 Fd CIS had finally marched out and the barracks was handed over to the National Museum, it held the record for being the longest barracks in continuous military use in Ireland and Britain.

The Napoleonic era and the threat from France to the United Kingdom (of which Ireland became a part under the 1801 Act of Union), saw the increased construction of barracks and coastal defences such as Martello towers. An official account in 1801 shows that £57,717 14s 5d was spent in Ireland on the construction of new barracks in that year, while in 1813 the Barrack Office, Dublin published estimates of the total cost of all barracks either completed or in the process of completion. The total ran to £30, 479, of which the largest individual sums were incurred for barracks in Kilmainham (Richmond), Parsonstown (Birr), Templemore and Portobello (Dublin).

In terms of understanding how soldiers were stationed in Ireland, the MPD collection, where certain sheets include detailed architectural plans and tables of accommodation, helps to shine light on exactly how soldiers, animals and equipment were housed in Ireland in the 19th and 20th centuries. The architectural plans and elevations for Lusk Remount DepÁ´t, for example, give some indication of the role of horses (a remount being a replacement horse, generally for the cavalry) in the British army in the 19th century. In terms of statistics, an early 19th century list gives the total accommodation in 121 permanent and 171 temporary barracks (both infantry and cavalry barracks) as 73,462 personnel, including 2,525 officers and 70,937 other ranks (non-commissioned officers/N.C.O.s and private soldiers). No further accurate strength figures for the British Army in Ireland are available until 1859, when monthly data from individual units/regiments becomes available. However, part of an unverified series of annual strength data for the period 1802 to 1844 shows 11,961 personnel in Ireland in 1802; 22,780 in 1822 and 21,251 in 1844. On 1st of Dec 1844, a total of seven cavalry regiments and thirty-one infantry units, including depÁ´ts, were stationed in Ireland.

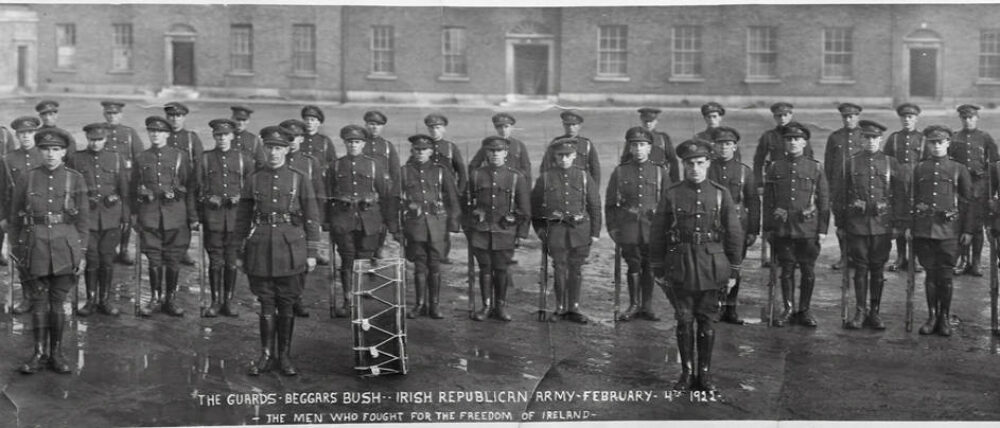

The strength of the British Army in Ireland before the handover of the barracks (which occurred following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921) tells its own story. On 1st October 1921, there were 57,116 personnel, an increase of 8,376 on the October 1920 figure and of 22,834 on the 1913 figure. The evacuation plan for the British forces envisaged that troops would be concentrated in Victoria (now Collins) Barracks, Cork, at the Curragh camp (containing seven separate barracks and now the Defence Forces Training Centre) and in Dublin city barracks, and that the evacuation would occur in that order . Once the Truce had been signed, the first barracks to be evacuated was at Clogheen, on 25th January, 1922. The last military post to be handed over to the Irish Free State (excluding the treaty ports in 1939) was the Royal (now Collins) Barracks in Dublin, on 17th December, 1922.

History and Provenance of the Collection

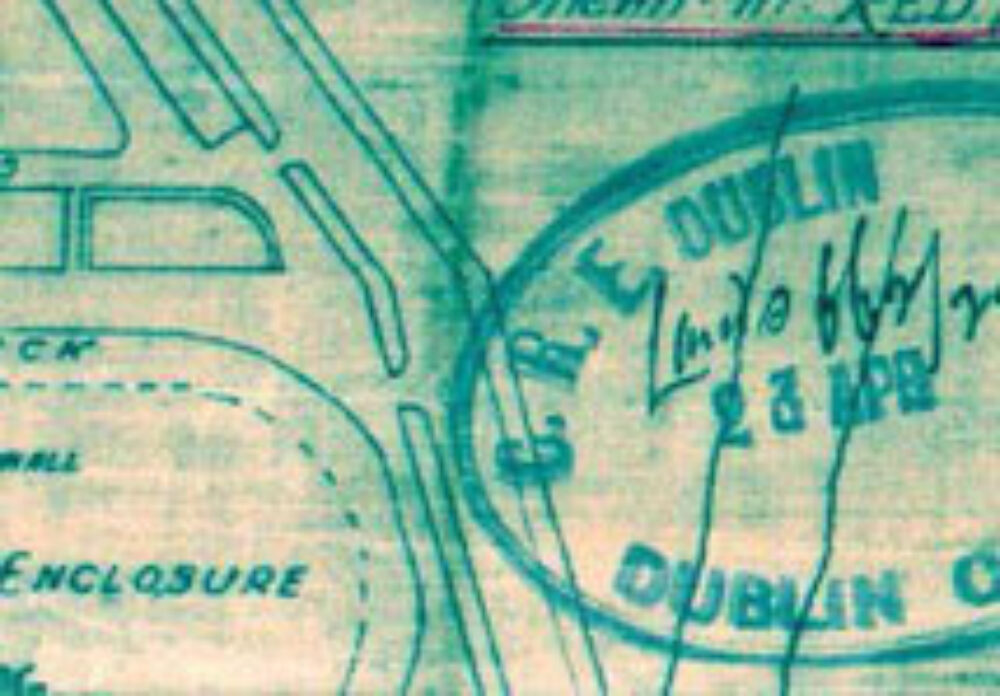

In the decades following independence in 1922, the Defence Forces’ Engineer Corps produced updated maps and plans, and of course a number of barracks were constructed in the modern era, typically in border areas (for example Monaghan Barracks). It is important to remember that military barracks were almost universally renamed after Independence, for example Islandbridge Barracks in Dublin became Clancy Barracks. However, the provenance of a particular architectural drawing cannot be guaranteed by reference to the name of the location alone. Portobello Barracks in Rathmines, Dublin, for example, was only renamed Cathal Brugha Barracks as late as 1952. Indeed, many of the earlier Engineer Corps plans show evidence of re-use of Royal Engineer Corps originals, but have the original name for the location erased and the Irish name inserted instead. The signature of the engineer officer responsible for a particular drawing is usually located in the bottom right corner of a sheet.

Military Archives typically acquires maps, plans and drawings from a variety of sources, including the Defence Forces’ Engineer Corps, Air Corps and Naval Service sources, units returning from UN-mandated missions overseas and private sources. The vast majority of the records in the MPD collection however were acquired by Military Archives in the early 1980s, from the Office of Public Works headquarters in St. Stephen’s Green, under the supervision of the then Officer in Charge, Commandant Peter Young (RIP). The maps were held at Military Archives for use by researchers in tandem with other documentary departmental and Defence Forces’ records such as subject files on the construction and repair of barracks.